Line drawing, like writing, can be declamatory or expository; a way of persuading viewers or a means to simply engage with the world beyond the self. The searching, tentative quality of a sketch is more like a soliloquy than a sermon, the artist’s interior dialogue groping toward a mystery. John Berger wrote that for Vincent Van Gogh drawing was “a way of discovering and demonstrating why he loved so intensely what he was looking at…”

At the beginning of a drawing class we focus on line and all of the various ways it can be played. Working with line is like the visual counterpart of MTV’s “Unplugged” series where musicians leave all their technological wizardry at the door and just play the music. In the absence of recording-studio colors and effects, the integrity of the basic idea is revealed. The ensemble stands or falls in that clarifying light.

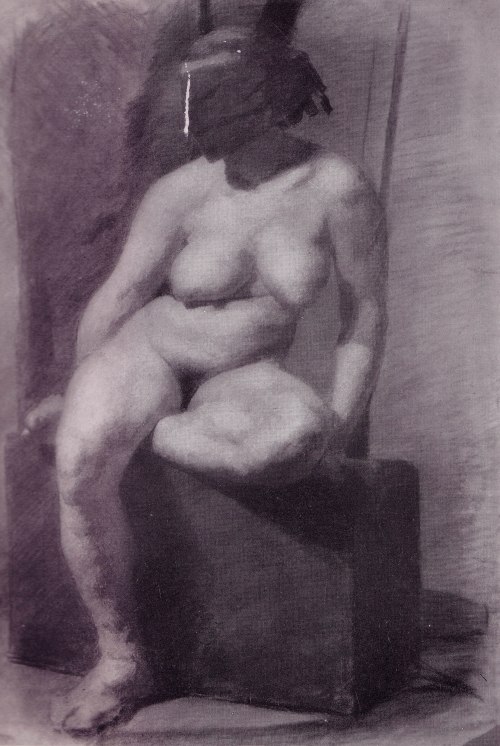

A linear drawing builds its riffs from a similarly austere palette, drawing its unique power from elimination, reduction, and distillation of the rich sensory experiences of the eye. Unaided by the seductive romances of tone, color and texture, the play of line in a drawing can inform us about what we are and are not seeing, allowing us to address problems before they’re embedded in complicated visual embroideries. The relative spatial positioning, directional movements, and scaling of one part to another can be tested and worked out. Like a house under construction, a line drawing is more about the foundation than about the furnishings. The understanding of relational structure, built over time through constant practice, is the foundation of our powers of expression as artists.

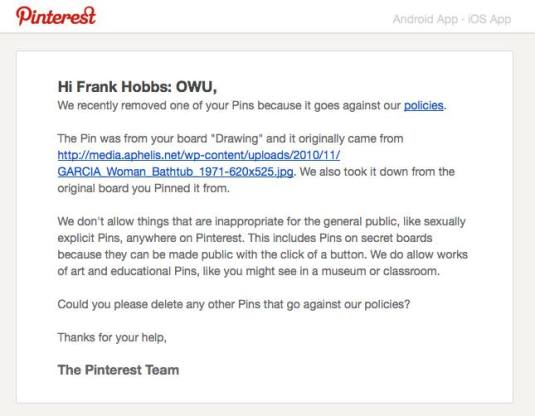

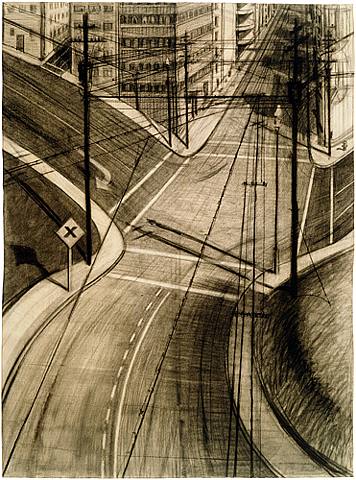

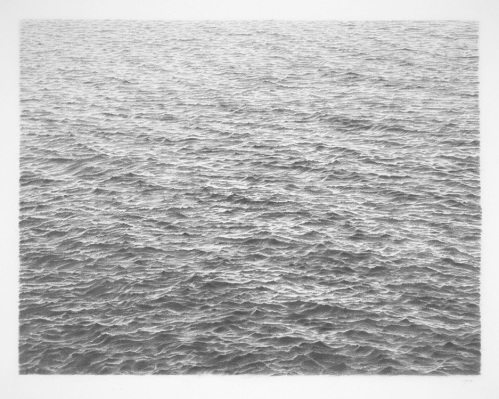

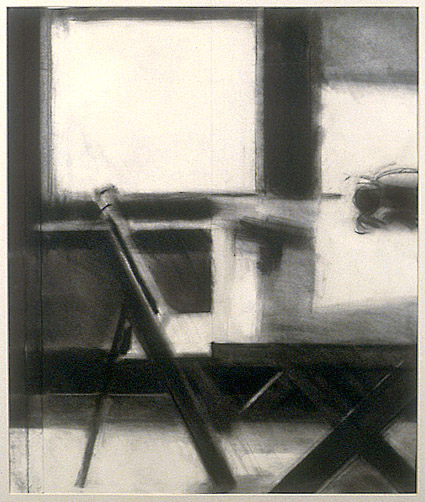

On its march toward resolution and clarification of intent a linear drawing leaves in its wake a clamoring of linear hypotheses that can produce a remarkable beauty, as can be seen in many of the drawings below. The ghostly images of abandoned positions, proportions and directions function almost like the sonic qualities of reverberation in music. Tonal drawings have an epic feeling and grandeur about them. Linear drawings, by embracing certain constraints on their means, can achieve a very different kind of poetry, not unlike the sparse syllables, internal rhymes and rhythms of haiku.

Tone speaks directly to the emotions. Line speaks to the mind. Or, rather, it speaks to the emotions through the mind by distilling the idea of the thing. Lacking the mimetic immediacy of tone, which is a closer approximation of the actual way that we perceive the world, the abstractness of a line drawing can never look like its subject in any literal sense. It can only look like itself, however much it may remind us of things seen. But, what we give up to line’s austerity, we gain back from its unique power of transformation. When we begin to draw, the motif is, as Henry James said of nature, a “blooming buzzing confusion.” As our lines negotiate and articulate that empty space everything changes – our perceptions, our emotions, even the motif itself. The provisional becomes the inevitable.